Sacred Sites of Corsica

Cauria megalithic site, Corsica

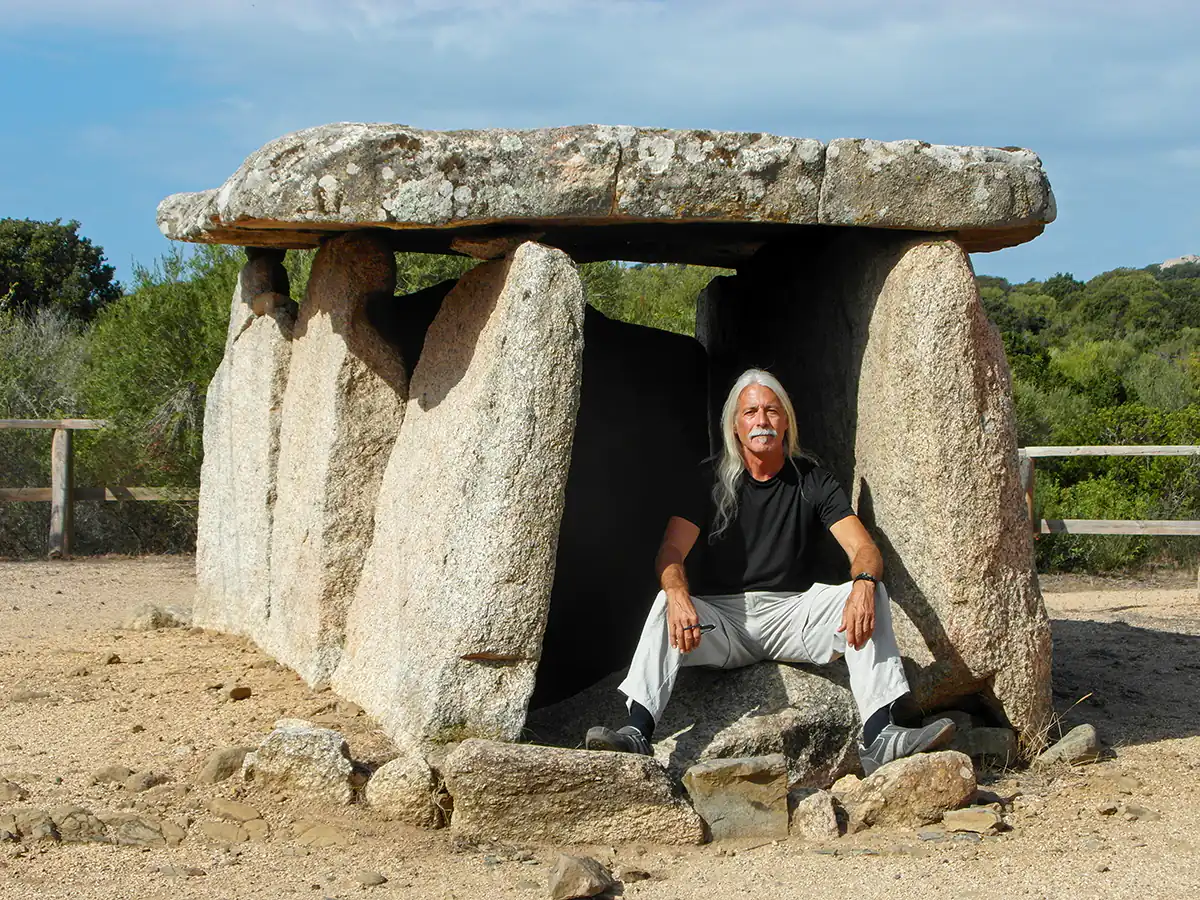

Stantari and Renaggiu menhirs, Fontanaccia dolmen

Scattered across the thinly populated hills of southwestern Corsica are numerous megalithic sites dating from as early as the fifth millennium BC. Little studied, the identity of their builders and purpose remains mysterious. A comparison to similarly shaped prehistoric structures in continental Europe suggests the Corsican alignments of standing stones, or menhirs, were used for astronomical observations and the chambered mounds, or dolmens, were used for ceremonial or healing purposes. A common misconception perpetuated by tourist guidebooks is that the human skeletal remains found inside and around a few of the dolmens indicate their use as funerary chambers. There is, however, no archaeological evidence to support this notion. The stone structures are far older than the bones found inside some of them. An ancient culture built the dolmens, while more recent people used them as convenient, already excavated places suitable for burial of the dead.

A unique feature of some of the Corsican standing stones, which may reach thirteen feet in height, is their depiction of human anatomical features, such as faces, shoulders and hands, as well as swords and daggers. A wide variety of megalithic standing stones have been found in other parts of Europe, but few with such clearly defined anthropomorphic features as those of Corsica. Some of the finest megalithic remains in Corsica are found at Cauria, Palaggiu and Filitosa.

Known to locals as Stazzona del Diavolu (the Devil’s Forge), the Fontanaccia Dolmen is considered the best-preserved dolmen in Corsica. Nearly two meters high, with six huge granite blocks supporting its great stone roof, it was once entirely covered by an earthen mound, long since eroded away.

The two lines of standing stones in the Stantari Menhirs are aligned in a north-south direction. All of the stones are featureless, except for two that have roughly sculpted eyes and noses, and swords shown diagonally across their fronts. Nearby are the other Cauria menhirs called Renaggiu.

Church of Santa di U Niolu, Casamaccioli

Hidden deep in the craggy granite mountains of north central Corsica, the small village of Casamaccioli is home to a legendary statue of the Virgin Mary, known as the Queen of Heaven or Santa di U Niolu. Perched on the side of Calacuccia Lake with magnificent views of Cinto massif to the northwest, the village hosts a three-day festival each September 8 that attracts more than 10,000 pilgrims.

The story of the miraculous statue began on a stormy night in the 15th century when a ship was blown off course between the island of Corsica and Italy. The situation seemed hopeless and the ship’s captain prayed to the Virgin Mary for assistance. In his despair he vowed to donate the most beautiful statue of the Madonna he could find in Genoa (some sources say in Naples). Immediately a strange light appeared above the Franciscan Monastery in the Tafonata forest of southeastern Corsica. The captain saw this as a sign, a message from the Divine Mother. He kept his promise and a statue was later placed in the monastery church. Miracles began to be reported from this time. During the 16th century, when Turkish pirates destroyed the monastery, the statue of the Madonna was saved. First it was taken to the church of Our Lady of Stella Pigna in Balagne in the north of the island, and thereafter was taken by mule deep into the mountains of the Niolu region. When the mule reached the village of Casamaccioli it refused to move further. The statue was placed in the Chapel of Saint Antoine near the cemetery. The next day it miraculously reappeared in the middle of the village. After this had happened several times, the Niolu shepherds built a church dedicated to the Virgin. Ever since that day, Corsicans have celebrated the festival of the Nativity of the Virgin.

The festival begins with a morning religious service celebrated on the square in front of the church. The colorfully painted wooden statue of the Virgin Mary is brought from within the church and placed next to an old crucifix in front of an altar. As the mass begins, a group of five men sing the Paghjella, a traditional chant. Following mass, dozens of white-robed men, drawn from local religious brotherhoods, or Cunfraternita, carry the holy statue around the village square in a complex route that winds and unwinds in spirals around the crucifix. Called the granitula, it is a procession that has its roots in the shamanic traditions of Pre-Christian times. When considering religious matters in Corsica it is important to understand that the island, particularly its mountainous areas, has for millennia been steeped in shamanism. The Christian practice of pilgrims at Casamaccioli walking the spiraling path around the cross – while holding the holy statue – is simply a re-enactment of a prehistoric shamanic ceremony.

Following the religious events, the exciting three-day Niolu fair begins. It is a time of feasting, drinking, song and dance. There are stalls where meats, cheeses, wines, honey, and other local products are sold. In former times, the festival provided the main opportunity of the year for peasants from remote villages to buy, sell and barter. In exchange for locally produced items, they could obtain hardware, hats, horse tack, woodcarving, textiles, shoes and anything else that could not be manufactured in the mountains.

One of the most interesting events at the fair is the Chjam' è Rispondi, a sort of verbal jousting competition held among the mountain shepherds. One shepherd will sing a challenge (Chjama) and another will respond (Rispondi) in the same melody and also in rhyme. It is quick, back and forth, full of wit and humor, and the singer who is best at expressing himself is rewarded by applause and laughter from the audience. The verses sung by the older men are often full of surprisingly beautiful poetry. Gambling is also a central part of the festival, with card sessions held in unlicensed home casinos all through the day and night. It is not unusual for some shepherds to gamble away parts of their herds after a night of heavy drinking.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 160 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.