Damascus

Great Mosque of Damascus, Syria

Located in the heart of the teeming city of Damascus, the Great Mosque is known to be the oldest existing monumental architecture in the Islamic world. For millennia before the birth of Islam, however, the city of Damascus was a sacred site of ancient and long-forgotten cultures. Some scholars think Damascus is the oldest continuously settled city in the Middle East and, as such, would have witnessed scores of different religious cultures. The recognized history of the temple site goes back to at least 1000 BC when the Aramaens built shrines for Hadad, the god of storms and lightning, and the goddess Atargites (Venus). Upon the foundations of these Aramaen sanctuaries, the Romans built a massive temple for the god Jupiter. Excavations done in the early 1900s have revealed rock inscriptions that give construction dates for the Jupiter temple of AD 15-16 and 37-38.

The Jupiter temple, which has almost completely disappeared (or is buried deep beneath existing structures), stood upon a platform known as a temenos (or sacred enclosure) that measured about 385 meters (421 yards) from east to west and 305 meters (334 yards) from north to south. The outer walls of the temenos still survive and are distinguished as large blocks of dressed masonry. At the four corners of the temenos, there were large square towers, of which only the southwestern survives, and around the edge, there were arcades that opened upon a large rectangular courtyard. Under the Roman Emperor Theodosius (375-95), pagan ceremonies at the temple of Jupiter were forbidden, Christianity took possession of the temple area, and construction was begun on a church of St. John that was situated in the exact place where the Jupiter temple had previously stood. This church, an important pilgrimage site of early Byzantine Christianity, continued to function even after the Islamic conquest of Damascus in 636. Following their occupation of the ancient city, the Muslims shared the great Roman temple platform with the Christians, the Christians retaining possession of their church, and the Muslims using the southern arcades of the Roman temenos area for their prayers.

In 706, al-Walid, the sixth Ummayad caliph, demolished the church and constructed a mosque along the southern wall of the Roman temenos. Using thousands of craftsmen of Coptic, Persian, Indian, and Greek origin, the construction took ten years to complete and included a prayer hall, a vast courtyard, and hundreds of rooms for visiting pilgrims. The triple-ailed prayer hall, roughly 160 meters long, was covered with a tiled wooden roof and supported on reused columns taken from Roman temples in the region as well as the Church of Mary at Antioch (a similar practice yielded columns for the mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia). The entire facing of the courtyard and the arcades surrounding it were embellished with colored marble, glass mosaic, and gilding, and, in fact, were the most extensive area of wall mosaic ever created in ancient times.

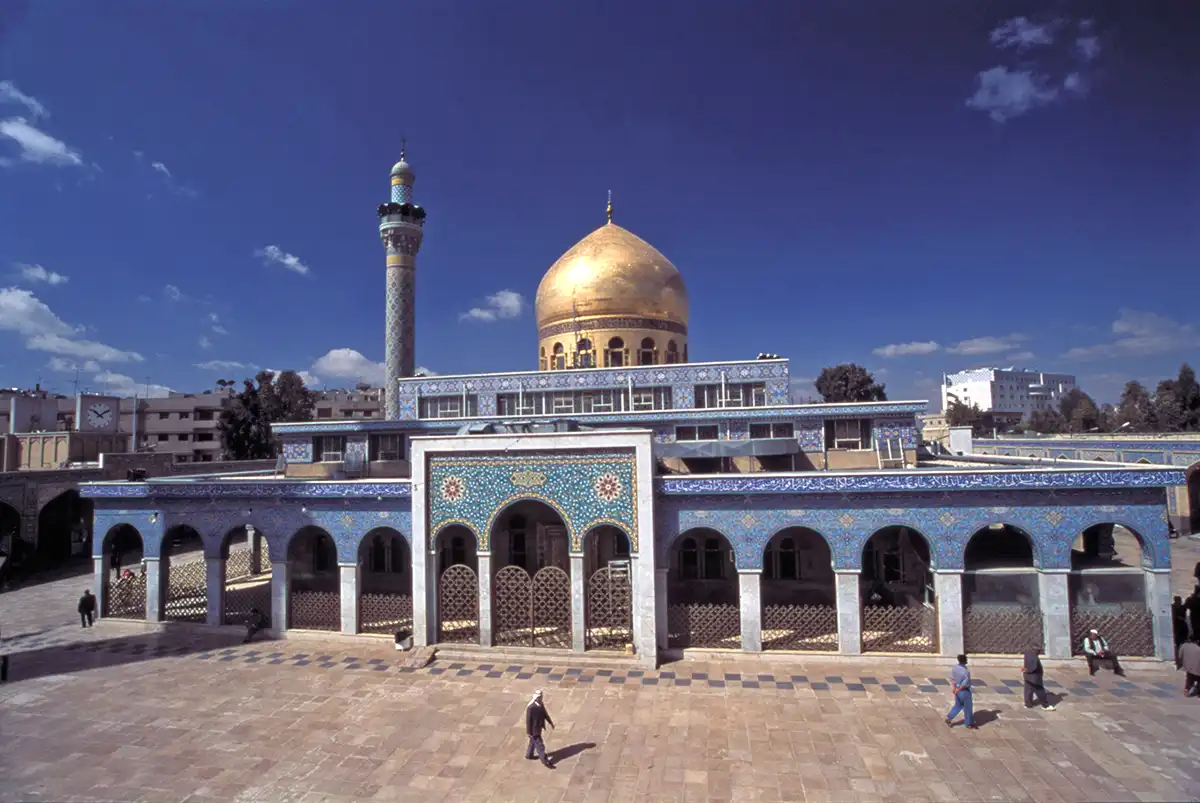

All that remains of this original Islamic ornamentation may be seen on the north outer face of the transept, under the gable, on the arcades and back of the west portico, and on the arches of the vestibule. The minaret structures of the current mosque compound developed out of the corner towers of the ancient Roman temenos. The existing minarets date from the time of al-Walid, with reconstruction and enlargements done around 1340 and 1488. The minaret of the southeastern corner is called the Minaret of Jesus because of a local tradition that says this is where Jesus will appear on the Day of Judgment. Since the Ummayad period of its construction, the mosque has been rebuilt several times in response to the disastrous fires of 1069, 1401, and 1893. The entire marble paneling that may be seen in the sanctuary today dates from after the fire of 1893.

Inside the mosque is a small shrine of John the Baptist (Prophet Yahia to the Muslims), where tradition holds that the head of John (and perhaps his entire body) is buried. Adjacent to the prayer hall, along the eastern wall of the courtyard, is the entrance to a finely tiled shrine chamber. According to different traditions, this shrine holds the head of Zechariah, the father of St. John the Baptist, or the head of Hussein, the son of Imam Ali (the son-in-law of Muhammad and the fourth of the 'Rightly Guided Caliphs').

There are several other shrines in the Damascus area including:

- The Shrine of Ibn Arabi

- The Cave of the Seven Sleepers, on Mount Qaysun

- Masjid al-Qadam (Mosque of the Prophet’s Footprint)

- Shrine of Lady Zeinab

- Shrine of Lady Roqauya

- Shrine of Lady Sokeina

- Shrine of Sakeer Bab

- Shrine of Sokina Bint Imam Ali

- Shrine of Abdollah Bin-zein-Abdin

- Shrine of Bilal al Habashi

- Shrine of Abdollah Bin-Jafar

- Shrine of Hijr Bin Oday

- Shrine of Habiba Waum Muslima

- Shrine of Fatima Bin Housein

- The cave of Ashab al-Kahf on Salera hill

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 160 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.