Chalma

Twenty-five kilometers west of Cuernavaca is situated the Pre-Columbian sacred site of Chalma. While its early history is shrouded in myth, it seems that when Augustinian friars first visited the area in the mid-1530s, they learned that local Indians were making pilgrimages to a sacred cave named Chalma. The pilgrims would walk for days through the surrounding mountains, wearing flowers in their hair and carrying incense burners, to make offerings to a statue of Ozteotl, the Dark Lord of the Cave. This statue was said to be a large, human-sized, black, cylindrical stone reputed to have magical healing powers. The god was variously identified as a deity of human destiny or of the night, sometimes taking the form of a jaguar or with the god of war, depending on different Indian oral traditions. The arriving pilgrims bathed in a river fed by a sacred spring and drank holy water before entering the cave.

When the friars were taken to the cave to see the stone statue, they found flowers, other gifts, and evidence of blood sacrifice. In 1539, Fray Nicholás de Perea gave a sermon to the Indians, preaching the evils of idol worship and blood sacrifice. When the friars returned to the cave three days later, it had been cleaned and whitewashed. The flowers were still there, but the image of Ozteotl was in pieces on the floor. In its place was a life-size image of a dark Christ on the cross. Seeing this, the Indians reportedly fell into "a wave of apostolic piety" and thus began the conversion of the natives in this region. According to another version, two friars arriving at the cave soon after the Spanish invasion destroyed the Indians' idol. They returned with a wooden cross to put in its place, but miraculously, so the legend goes, there was already a crucifix with a black Christ, and the entrance was full of exquisite flowers. Still, other sources say that the Augustinian friars sculpted the archaic stone into the shape of Jesus Christ.

Before long, the cave entrance was enlarged, and a shrine was dedicated to St. Michael. The image of Christ remained in the cave for 143 years, but in 1683, it was brought down to a church specially consecrated for its worship, which became the first sanctuary of Chalma. This new church was given the official name of El Convento Real y Sanctuaria de Nuestro Senor Jesus Christo y San Miguel de los Cuevas de Chalma (the Royal Monastery and Sanctuary of Our Lord Jesus Christ and Saint Michael of the Caves of Chalma) under the protection of Charles III of Spain. In 1830, the sanctuary was renovated. From the middle of the 16th century, hostels were built to accommodate pilgrims. The original Christ statue of Chalma was destroyed by a fire in the 18th century, and the image that is venerated today is modeled after its remains.

Thousands of Catholic pilgrims flock to the site throughout the year to give thanks for prayers answered or to make wishes. While some other Mexican pilgrimages involve self-flagellation and suffering, with penitents hobbling on bleeding knees, pilgrims to Chalma pray through dancing. Today’s pilgrims follow each other along the same narrow paths they have for centuries. They take a route through Cuernavaca, then cut through back roads and continue cross-country to Chalma. Many walk the last leg of their journey at night, the glittering light from their torches and candles snaking a magic trail up and down the deep ravines. Women carry small babies; older men hope for a miraculous cure; and young folk seek an adventure. They wear flowers, just as their ancestors did, and many crawl on their knees for the final part of their journey.

The peregrinos (pilgrims) arrive in Chalma in time for a hearty breakfast and early mass, and then relax a while in small plazas around the church before the journey home. At the back of the church, behind the monastery, flows a stream - where people still bathe in water from the same spring that fed Ozteotl's cave. Here, a wall is overcrowded with simple paintings, photos, locks of hair, and other personal tributes displayed as thanks for miracles granted. Upon entering the charming baroque church, pilgrims light a candle and place a milagro (small metal talisman) in a box before the altar. The most significant number of pilgrims make the journey for Lent to receive the ashes at mass on Ash Wednesday. Just as the adherents to Our Lady of Guadalupe are called Guadalupanas, the devotees of the cult of Our Lord of Chalma proudly call themselves Chalmeros.

Most pilgrimages are well organized. Some parishes have tee shirts and unique clothing produced for the annual pilgrimage. However, you will sometimes see groups of pilgrims wearing traditional clothing from their region. Trucks from the village sometimes accompany a group carrying food and camping supplies and assisting the old and tired. The trucks are brightly decorated with banners and intricate flower arrangements.

The pilgrimages to Chalma take some time for preparation. One month before the journey, pilgrims meet at the house of the captain to discuss and arrange all the preparations. The night before the departure, they may gather in the captain's house or meet at a certain point to go together. Before, the pilgrimage was done on foot; sometimes, it is still done this way, or walking is combined with cars and buses. On the way, there are houses for pilgrims or private homes where they are given lodging. Many groups of pilgrims have carried the image of their patron saint from their village, covered by a blanket during the pilgrimage. At the church, it is uncovered by the pilgrimage captain, who incenses it and sings some praises.

Chalma’s town is on one side of the sanctuary and has grown as its shadow. It is surrounded by cliffs crowned by crosses, some over seven meters high, which were placed there to scare the evil spirits. Each cross belongs to a group of devotees. They are brought down to the atrium every year, painted and ornamented, and then taken up again. When the cross is placed on the top of the hill, their dancers dance around it and spend the night guarding it, singing, and lighting artificial lights. The shrine has spawned an industry, with stalls selling religious trinkets and plastic bottles for the spring water. Rich aromas of Mexican fare waft from makeshift restaurants where hungry pilgrims, many of whom travel two or three days across the mountains from Mexico City, stop for a bite to eat.

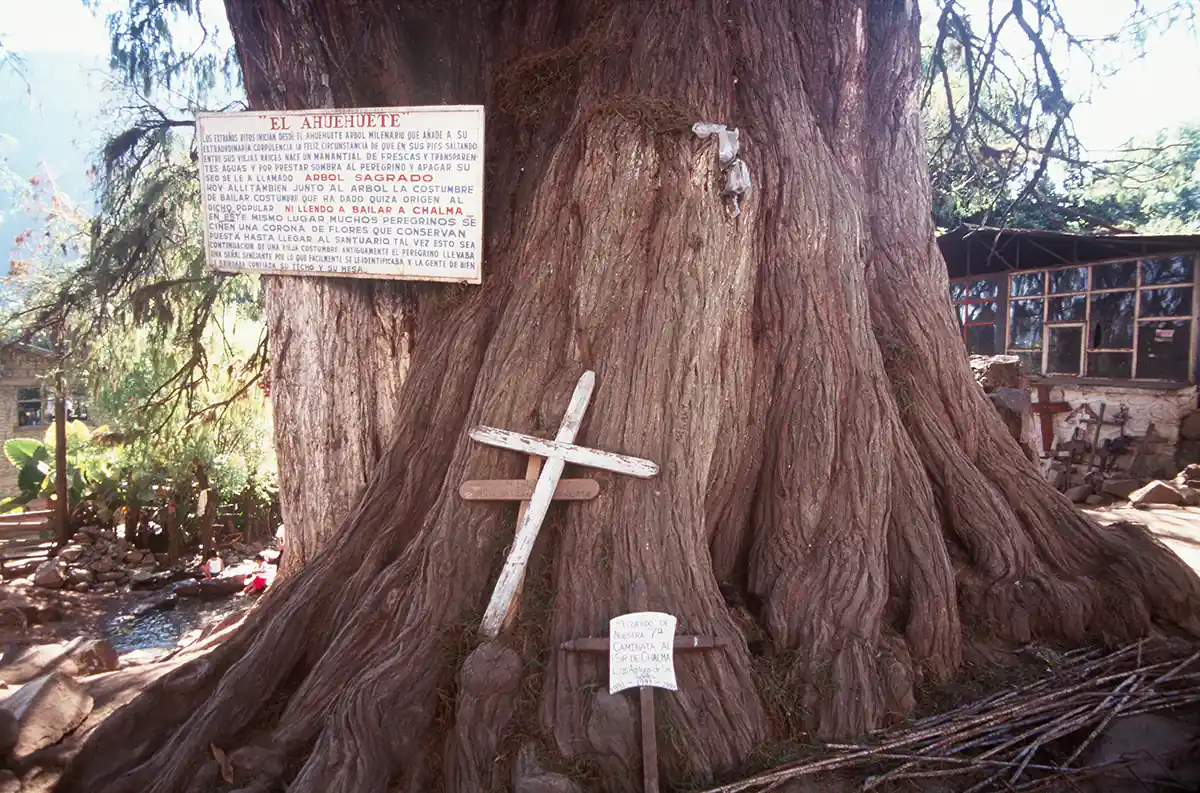

Near Chalma is an enormous 1100-year-old cypress tree called the Ahuehuete, meaning 'old man of the water' in Nahuatl, an indigenous language of central Mexico. From beneath the roots of the tree flows a revered sacred spring. In the tree's branches, pilgrims place notes and items reflecting their prayers and small bags with newborn babies' umbilical cords to give thanks for a successful birth. Women gather water from the spring and pour it over their bodies in hopes of becoming fertile. In an expression of joyful spirit, many pilgrims wear crowns of flowers and dance as they offer prayers.

"We come here every year," said Antonio Marillo Reyes from central Hidalgo as he and thirty relatives enjoyed a picnic beside a spring gushing from the tree's roots. "All the babies in our family have been thrown in the spring water but it doesn't harm them. We are praying for work and good health."

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 160 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.