The Incan Empire

The INCA and their History

At the time of Columbus' landfall on the New World, the greatest empire on earth was that of the Inca. Called Tawantinsuyu or 'Land of the Four Quarters,' it spanned more than 4300 miles along the mountains and coastal deserts of central South America. The vast empire stretched from central Chile to present Ecuador-Colombia border and included most of Peru, Bolivia, Ecuador, northern Chile and northwestern Argentina (this is a land area equal to the entire portion of the United States from Maine to Florida east of the Appalachians). It exceeded in size any medieval or contemporary European nation and equaled the longitudinal expanse of the Roman Empire. Yet for all its greatness, Tawantinsuyu existed for barely a century.

The origins of the Inca are shrouded in mystery and mythology. According to their own mythology, the Inca began when Manco Capac and his sister, Mama Occlo, rose out of Lake Titicaca, having been created by the Sun and the Moon as divine founders of a chosen people. Manco Capac and his sister then went off with a golden rod to find a suitable location to found a great city. Through a series of adventures, geomantic resonances, and astronomical correspondences, the site of Cuzco was chosen.

Archaeological research, on the other hand, indicates that the pre-imperial Inca were simply one of a number of petty tribes in the south central region of Peru. From roughly 1200 AD to the early 1400's, the Inca engaged in numerous battles with local rivals, but never achieved supremacy over any of them. Around 1438, however, the Inca emperor Viracocha and his son, Pachakuti, defeated a powerful rival, the Chankas. From this time the empire building era of the Inca began. Other rival tribes around the Cuzco area were soon united and campaigns were launched into the Titicaca basin and beyond. During the ensuing reigns of the emperors Pachakuti, and Topa Inca the Inca armies expanded the frontiers of Tawantinsuyu from southern Columbia to central Chile.

In the few short years before their overthrow by the Spanish in 1532, the Inca developed one of the largest and most sophisticated empires in the entire pre-industrial world. (In discussing Inca achievements, however, it is important to state that they were not the singular invention of a few inspired emperors but rather the ultimate elaboration of numerous pan-Andean institutions.) The Inca accomplished their phenomenal growth through a mixture of diplomacy and warfare, and a sociopolitical management system based on highly effective taxation and the dependable provision of goods and services to the peoples of their realm.

As the Inca began to expand their territories, the first step was to seek alliances with tribes upon the frontiers. Copious gifts of textiles, exotic products from distant regions, and wives to add blood ties to the alliances were offered to the chiefs of these tribes. Quite frequently these gifts were readily accepted (certainly the intimidating specter of the powerful Inca armies assisted in this process), but if certain tribes proved recalcitrant, the Inca simply overwhelmed them with superior military power.

In either case, the tribes were then incorporated into larger administrative units and political provinces. This strategy left Tawantinsuyu with more than 80 political provinces, each with different ethnic and linguistic characteristics. To address these regional differences the Inca imposed there own tongue, Quechua, as the language of the realm and the medium of governmental communication. Additionally, the Inca frequently moved entire populations around their realm, putting loyal groups into troublesome areas, and transferring recalcitrant tribes to loyal areas. These wholesale transfers of people were also used to introduce weavers and farmers, stone workers and artisans into areas where these skills were needed.

Inca statecraft, a system of truly extraordinary efficiency, was founded upon the ancient, pan-Andean concept of reciprocity. Goods and services moved from the local area to regional and state warehouses and were then redistributed back to the populace in several important ways. The state economy was based, not on currency systems, but on extracting taxes in the form of labor. There were three primary forms to this taxation: agricultural levies on local community-managed lands; a labor service required of able-bodied males that provided for monumental construction projects and military campaigns; and the textile production required of women, children and older men. The goods and services gathered in these ways were then divided into three shares. The first third went to support Inti (the Sun god), other gods in the state pantheon, and a wide variety of ceremonial activities. The second portion went to support the Inca emperor and the construction and military projects he initiated. The third portion was redistributed to the common people in the form of food, textiles, lavish festivals, and military protection.

The most visible, and remaining, examples of Inca genius are to be found in their monumental construction projects: in the form of roads, agricultural terraces, and administrative and ceremonial structures. The vast empire was united by an extensive and superbly efficient highway system. Two parallel highways, one along the coast and the other in the high mountains, ran north-south from one end of the empire to the other. Between these two major highways ran dozens of east-west roads linking the coasts, mountains, and jungles. Altogether there were more than 30,000 kilometers of these roads, the majority of which were beautifully paved, well drained, and equipped with storage houses, travelers' lodges, and military posts. The produce of the empire moved efficiently along these roads, transported by hardy llamas strung together in caravans of a thousand or more animals. Furthermore, along the roads sped the most rapid communication system ever developed in the pre-industrial world; in the form of a constant movement of fleet-footed runners.

To feed the people in their swiftly growing empire, the Inca terraced great areas of mountain land, transported rich soils to the terraces, employed highly sophisticated irrigation systems, and experimented with a variety of crops. These monumental landscaping projects, called andenes in the Quechua language, so impressed the colonial Spanish that they named the Andes mountains after them (recent satellite photography has shown that these Inca terraces covered more land than is currently cultivated in the central Andean nations).

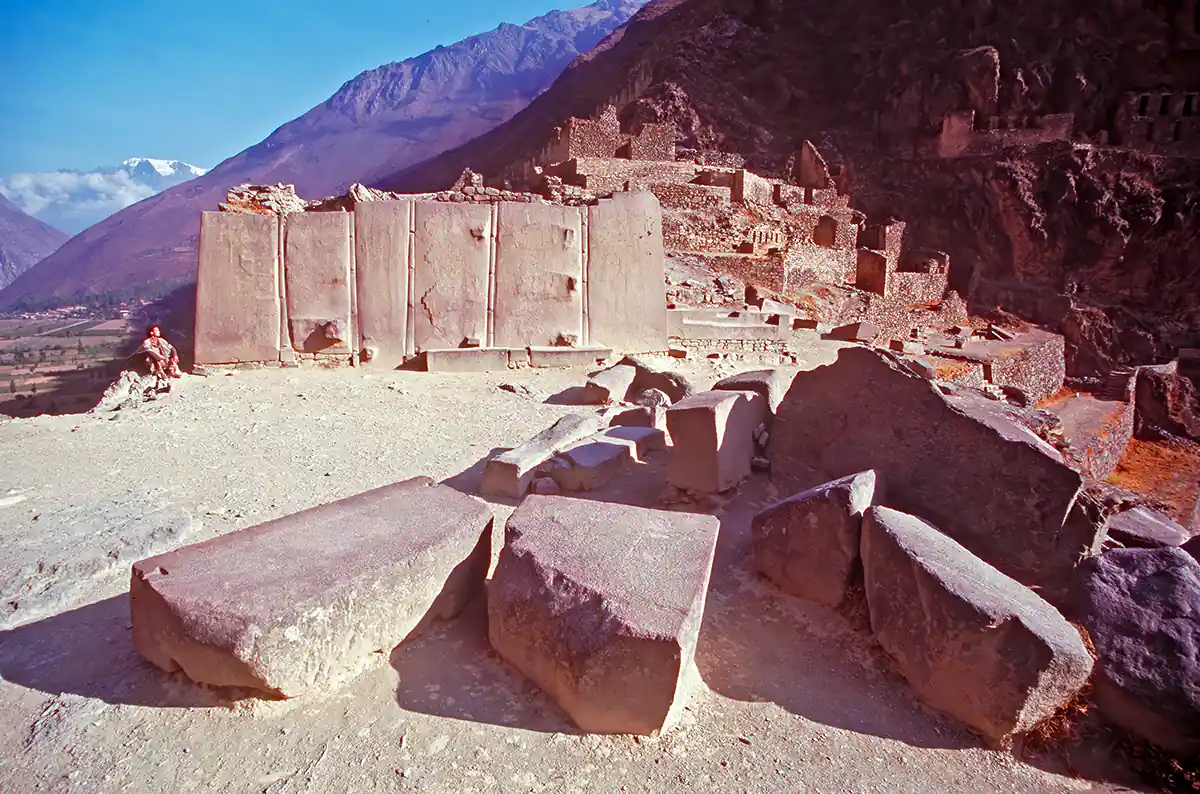

In their administrative and even more so, their ceremonial centers, the Inca most clearly displayed their brilliance with design and construction. Great surviving centers such as Pisac, Ollantaytambo, Machu Picchu, and Cuzco, the Inca capital, are well known examples. In these places the Inca fashioned monumental architecture equal in beauty to any culture of the old world. Massive, multi-sided blocks were precisely fitted together in interlocking patterns in order to withstand the disastrous effects of earth quakes (in an earthquake, the stones on Inca terrace walls lock together, allowing the entire wall to simultaneously flex and cohere). Both secular and sacred architecture had spacious windows, niches for idols, and other purely artistic sculptural elaborations. Splashing fountains abounded and masterpieces of hydraulic engineering brought fresh water into buildings, while other channels removed wastes.

The Incas never used the wheel in any practical manner. Its use in toys demonstrates that the principle was well-known to them, although it was not applied in their engineering. The lack of strong draft animals, as well as steep terrain and dense vegetation issues, may have rendered the wheel impractical. How they moved and placed the enormous blocks of stones remains a mystery, although the general belief is that they used hundreds of men to push the stones up inclined planes. A few of the stones still have knobs on them that could have been used to lever them into position.

It must be noted, however, that the places mentioned above, Pisac, Ollantaytambo and Machu Picchu in particular, are known to have been ceremonial sites many centuries and even millennia before the Inca developed and, furthermore, already had existing structures that were used for astronomical observations and ceremonial functions. Many contemporary people writing and speaking about the Inca are not well enough educated to know this matter yet, none the less, it is archaeological fact.

The name of the archaeological site Machu Picchu is sometimes misspelled as machu pichu, macchu picchu, machu piccu, machupicchu, macu picchu, macho picchu, machu piccho, machu picch, macha picchu, machu piccuh, mach picchu. The correct spelling is Machu Picchu.

Martin Gray is a cultural anthropologist, writer and photographer specializing in the study of pilgrimage traditions and sacred sites around the world. During a 40 year period he has visited more than 2000 pilgrimage places in 160 countries. The World Pilgrimage Guide at sacredsites.com is the most comprehensive source of information on this subject.